Last week I wrote a long post about my perspective on America’s epidemic of gun violence and then shortly afterwards, I had the opportunity to visit a gun range with some friends. I felt like it was my duty to challenge my assumptions about these weapons, to try to understand the passion people have of firearms, and to see if I could learn anything practical. Especially because this is a highly polarizing issue, I wanted to do what Adam Grant, an organizational psychologist, acclaimed professor at Wharton Business School, and best-selling writer, advocates in his book, Think Again — approach controversial issues with humility and a nuanced perspective.

Adam Grant has made a career out of helping people and businesses become more inspired, creative, and productive. His books have sold millions of copies. One in particular, Originals, is one one of my favorites because he explores how aspiring innovators can discover their great idea, manage their fear, and execute successfully. Along with Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers, it has been incredibly influential to me as I find my own voice as a creator. Grant also hosts a podcast called “Work Life,” and is also a fantastic speaker, whose TED talks have garnered millions of views.

Why Think Again Matters

I read his new book, Think Again, recently because I have been searching for better ways to learn, converse, and debate about contentious issues. It is now taken as fact that news and social media, with their increasing infusion of shock and fear mongering straight to America’s veins, have polarized our country. The comments sections on websites and social media apps are filled with derisive remarks and derogatory trolling that slowly devolved from normal discussions to outright personal attacks.

It comes as no surprise to me that people no longer want to discuss their personal views in public spaces, face-to-face, like we once did prior to the Internet. Once upon a time, public forums and town halls were spaces for us to debate how we wanted to improve and live together as a community and a country. These gatherings were not perfect, people of color and women were often excluded, but, for the most part, they had a protocol and an idea of how to conduct “gentlemen’s” discourse.

But we are unable to speak like that any longer. Our quest for pithy 140 to 280 character tweets and hot takes, the pace of news and pop culture events, and our shortening attention span and increasing isolation from each other have hindered our ability to communicate. Having these conversations about the liberties we should or should not have on guns, abortions, LGBTQ+ rights, police brutality, climate change, immigration, sex education, banned books, and so much more are rightly difficult. They are supposed to be because change and growth require discomfort. Anything that remains stagnant over time will eventually wither and die. This is hard-coded into the nature of the universe.

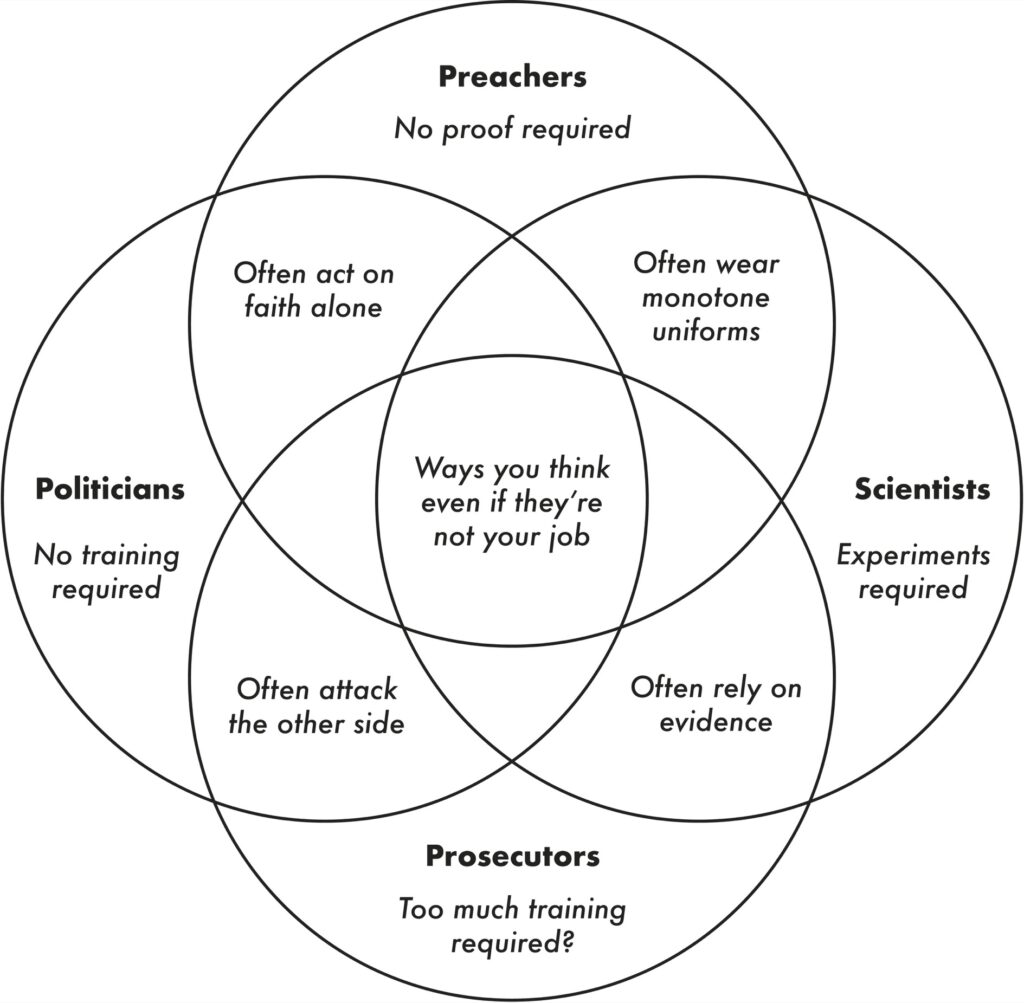

Think Again, however, is Adam Grant’s attempt to teach us how to rethink our ideas and beliefs. He advocates that we stop confusing feelings for facts, that we refuse to let our ideas become our identities and ideologies, and that we choose humility over pride. He references the work of political scientist, Philip E. Tetlock, who proposed that when we discuss our ideas, we shift between different modes, which Tetlock called “preachers, prosecutors, and politicians.”

Grant writes,

“We go into preacher mode when our sacred beliefs are in jeopardy: we deliver sermons to protect and promote our ideals. We enter prosecutor mode when we recognize flaws in other people’s reasoning: we marshal arguments to prove them wrong and win our case. We shift into politician mode when we’re seeking to win over an audience: we campaign and lobby for the approval of our constituents. The risk is that we become so wrapped up in preaching that we’re right, prosecuting others who are wrong, and politicking for support that we don’t bother to rethink our own views.”

Instead, Grant proposes that we think like scientists. He wants us to actively search for truth versus presuming understanding. He wants us to run experiments and test our hypotheses. He recommends doubting your first instinct and assumptions, and looking for clarification instead. Don’t mistake feeling right for being right, he cautions. He warns that just because you are smart, it does not protect you from falling for your confirmation or desirability bias. Grant notes that the higher a person scores on an IQ test, the more likely she is to fall for stereotypes, simply because she recognizes patterns faster.

Throughout his book, Grant reviews numerous studies and gives practical advice on how to divorce our convictions and embrace curiosity instead. So that is why, despite my perspective that guns and their owners should be registered, licensed, and carrying insurance, I spent an afternoon learning about firearms. I cycled many lessons from his book repeatedly through my mind as I spoke to the attendants at the gun range and practiced how to handle and shoot guns.

Lesson #1: Seek Out Information That Goes Against Your Views

The shooting range is located on the outskirts of Houston, under a large “Gun Range” billboard visible from the adjacent highway and the US and Texas flags flying overhead. The main entrance was tastefully outfitted with hardwood floors and wood-paneled walls. Merchandise like t-shirts, hats, ear and eye protection, and gun cleaning supplies sat on the racks in the lobby. A variety of pistols were displayed behind glass towers that were spread across the floor. Along the perimeter were long display cases with even more handguns; the larger rifles were presented on the walls just behind them.

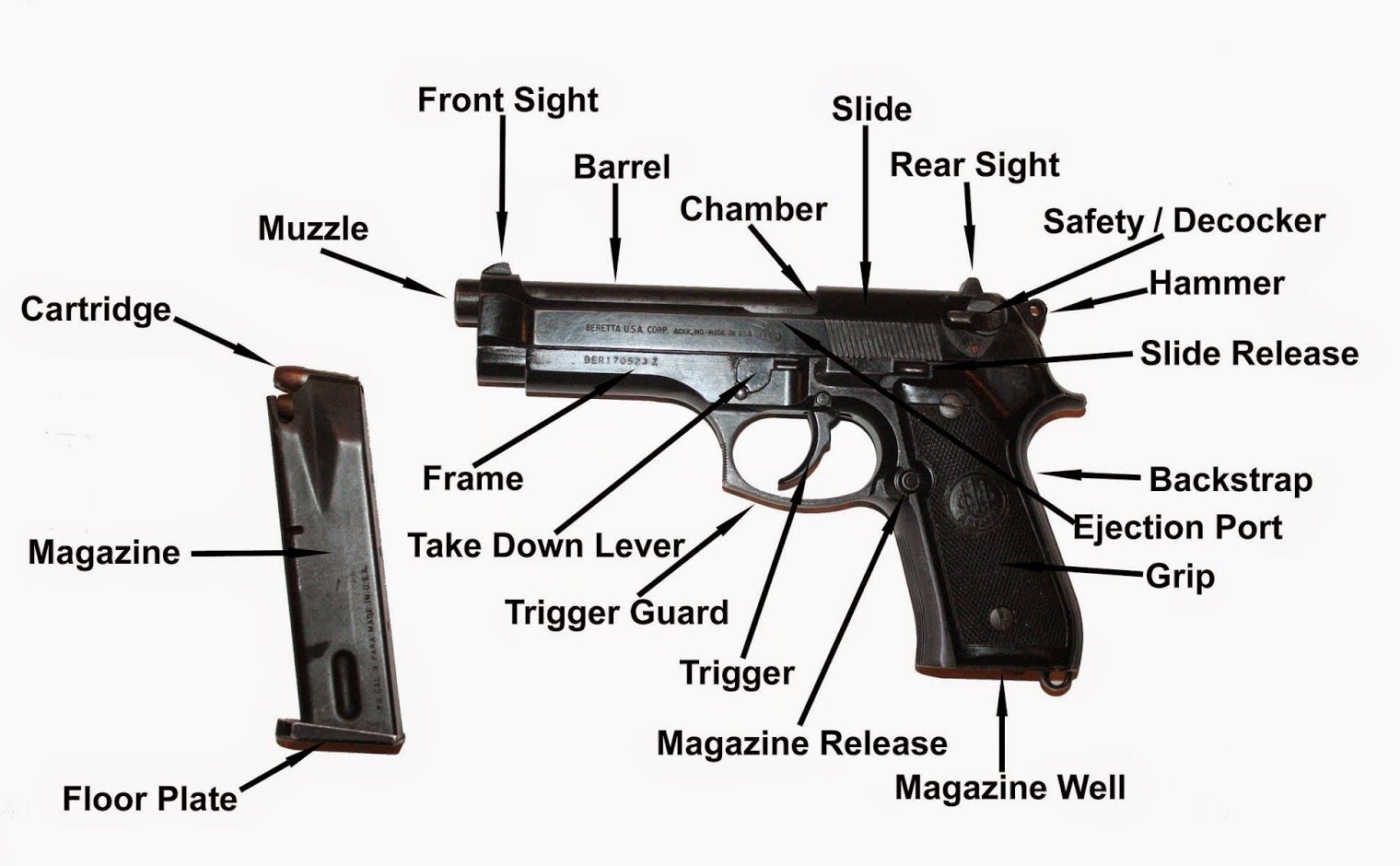

The first priority for my friends and I was to learn how to properly and safely handle a gun. The instructor was a young man in his late-20s to early-30s, kind, patient, and eager to teach. He emphasized that guns are important for feeling safe, but that it is essential to be comfortable with handling and firing them before purchasing one, which he recommended that we all eventually do. He showed us where to find the safety, how to properly hold the gun, how to release the magazine, and how to pull back the slide release to check the chamber for a cartridge.

He emphasized that with any firearm, there are four universal safety rules to follow:

- Always assume the gun is loaded, even if the magazine is removed and the chamber is empty.

- Do not point the gun at anything you are not willing to kill or destroy.

- Keep your finger off the trigger until you are pointing at your target and ready to shoot.

- Do not shoot at a target unless you know what is behind it.

After the brief tutorial, he helped us pick out a smaller-caliber 22 mm Glock, a larger-caliber 40 mm Glock, and ammunition at a discounted rate. He handed us ear plugs, eye protection, and paper targets. Then he wished us luck. “Once you are in your lane, if you need any help or have any questions, just turn around and wave your hand at the camera behind you. Someone will be there,” he assured us.

After this initial introduction, I felt more at ease in my new surroundings. Everyone we had met was welcoming and friendly, and the advice we received made sense. As a natural skeptic, I acknowledged that not only did he want us to be safe when using firearms, he was also working on recruiting new customers. I expected some hostility, especially because of the way I look and my name, but was happy that I did not perceive any.

We walked through two double-doors and were greeted with the occasional BANG of a firearm discharging, which caused us to repeatedly flinch each time. I am generally not a fan of loud noises and the sharpness and suddenness of the sound were especially hard to get used to. I jammed the ear plugs in and put on the ear protection I had purchased, which provided immediate relief.

As soon as we entered, an elderly gentleman, short and stocky, approached us, apparently sensing that we were beginners. He introduced himself as “Anthony”* and politely asked if we had much experience shooting guns before. We shook our heads. “That’s okay, I’ll teach you,” he smiled. One by one, he led us to the lane we rented and proceeded to expand on the lessons we were taught at the counter.

Lesson #2: Learn Something New From Each Person You Meet

Anthony stood with me in the lane and showed me how to properly hold the gun, how to feel its weight in my hand, how to ensure the skin between my forefinger and my thumb did not get caught in the slide release. He showed me how pressing a thumb release allowed me to remove the magazine. Despite my hands being larger than his, I found it challenging to use my thumb to press the release. “I feel like your hands are stronger than mine,” I remarked.

His eyes twinkled as he grinned. He held his hand out, as thick as a baseball glove. “I’m seventy-one years old. have been shooting for over sixty years, since I was ten years old. The strength comes with time.” He clearly enjoyed my reaction. He barely looked a day over fifty.

Next, he demonstrated how to pull back the slide release, which is harder than it looks, and check if a round was loaded and then had me practice. He taught me how to line up the rear sight and the front sight. “If you do it properly, the rear sight will be blurry and your target will be blurry. Only the front sight will be clear,” he said.

Finally, he had me load the weapon and train my sights on the target. “Stand with your weight evenly balanced. Bend your knees,” he advised. “Lean slightly forward and keep your arms out in front of you but don’t lock your elbows. A strong stance will help you brace yourself from the recoil.” He watched me practice my stance and guided my shoulders forward. “Now let it rip,” he ordered.

I stood with my feet shoulder width apart, my left foot slightly in front of my right. I slapped in the magazine, pulled back on the slide release, and listened to the cartridge load with a click, which I have to admit, sounded satisfying. Arms extended in front of me, Anthony guided my shoulders forward. My hands cupped the grip and I made sure to keep them clear of the slide release. I felt hyperaware about keeping my trigger finger on the side of the gun and not pointing the gun until I was ready to shoot. I closed one eye, leveled the gun, and tried to line up the sights. Then I fired.

A large BANG and the smell of smoke. The recoil caused my hands to lift slightly and the force traveled down my arms and into my shoulders. The cartridge shell pinged off the wall to my right. “A little high,” Anthony said. But at that point, I did not care that I had missed. So that’s what that feels like, I said to myself, the dopamine surging. I worked to line up my sights again and kept firing, listening to Anthony’s advice about how to achieve better accuracy. As soon as I felt like I was understanding what he wanted me to do, the gun clicked differently and I could no longer pull the trigger. I had already emptied the clip. As fast as I had started, it was over.

Lesson #3 – Ask How People Originally Formed An Opinion

We spent much of the evening trying out a variety of hand guns. The power in each of the guns differed and I found that the recoil of some were easier to control than others. The targets were set 15 to 20 feet away and I noted that with some dedicated practice, one could reliably hit their mark with accuracy.

A few lanes over stood a large man in a button-down and cargo pants. He was unloading a large, heavy duty duffel bag. Removing a large rifle, he checked its component parts and placed it on the counter. One of my friends caught me looking. “I invited my buddy. Let me introduce you.” he said. “He brought his AR-15.” I recognized the name. This was the same gun used in the mass shootings at Aurora, Las Vegas, Parkland, Newtown, and Uvalde — a gun synonymous with the mass murders of children and churchgoers and unarmed civilians. I felt like I had to try the gun, to see if I could understand why people felt so fanatic about it.

We walked over and my friend greeted the man before introducing me to “James”*. We exchanged pleasantries. Like everyone I had met so far that day, James was friendly and generous. He was also proud of his AR-15 and very knowledgeable about different types of firearms. “I started shooting when I was 10 years old and my family has always had guns. It’s just something that I felt drawn to,” he said. I learned that he was a member of the professional class, a hard-working and intelligent lawyer. He like to shoot guns to relieve stress, but he also occasionally liked to hunt.

He went on to talk about the different types of guns he owns, his hunting rifles and his pistols, and when and why he likes to shoot them. Then he began to teach me about his AR-15. He pointed out the safety, showed me the magazine, where it fitted into the gun, and how to release it. He showed me the rear sight and front sight, as well as the red dot sight for greater accuracy. He taught me how to hold the AR-15, fitting it in my armpit, between my shoulder and my chest, resting my cheek on the buttstock. The gun was heavier than I thought and trying to place my cheek so that my eyes lined up with the red dot sight took some time to get used to.

When I fired the AR-15, the power was evident, but the recoil was easier to manage as my hands were assisted by my shoulder to control the weapon. The rounds left larger holes in the target. James spent some time correcting my stance and gave me pointers for better accuracy. Each time, the magazine emptied faster than I expected. Each time I tried a new gun, the novelty over firing them faded. I could not help but think this hobby was similar to hitting expensive golf balls into the ocean or putting coins into a slot machine. The buzz was short-lived and you lost money each time you fired a round. I was not gaining new knowledge or getting into better shape. Eventually, I found myself standing back, watching and enjoying my friends’ reactions as they fired the guns. Shortly afterwards, an announcement over the intercom ordered “Cease fire.” It was time to close the shooting range for the night.

Lesson #4 – Complexify Contentious Topics

In its quest to analyze hundreds of environmental inputs a second, in order to maintain its ability to process new knowledge, the human brain has a preference to organize ideas, especially complicated ones, into simple black-or-white choices. They are easier to understand, make for better headlines, and give us some semblance of closure. Psychologists call this the “binary bias.”

Unfortunately, this is also where the polarization of society arises. The spectrum and complexity of views that exist between the extremes becomes lost, making it harder to empathize. News and social media take advantage of this phenomenon, attempting to shock and enrage us so that we are motivated to click and share more, enriching them further.

But how do we combat this? Adam Grant, in Think Again, explains,

“An antidote to this proclivity is complexifying: showcasing the range of perspectives on a given topic. We might believe we’re making progress by discussing hot-button issues as two sides of a coin, but people are actually more inclined to think again if we present these topics through the many lenses of a prism…

A dose of complexity can disrupt overconfidence cycles and spur rethinking cycles. It gives us more humility about our knowledge and more doubts about our opinions, and it can make us curious enough to discover information we were lacking. ”

There is a long and deep history of gun ownership in the United States. Without having grown up in an environment where guns are revered, it is sometimes challenging for me to understand their purpose outside of destruction. But I have to recognize that my lack of familiarity and wariness over firearms is not enough for me to make a blanket statement that guns are bad. I have to acknowledge that the acceptance of guns exists on a spectrum. Some want the most powerful weapons possible while others will take a more measured approach. Some would rather have guns because they were indoctrinated to instill fear in their neighbors, while others simply want them so they can bond with their children while they teach them how to hunt. Even though it might be frustrating at times to wonder why people continue to brandish their weapons, the reasons they do vary and the distress they feel about potentially losing them is real.

Some of the hardest challenges we have on a daily basis are navigating the difficult conversations about the contentious issues we face in our society, at work, or with our loved ones at home. How do we understand someone else’s perspective? How do we properly negotiate challenging circumstances so that everyone feels honored and heard? Grant reminds us that the onus is not always on the other party to change. More often than not, we have to take a look in the mirror at our own biases and understand our own motivations. If we want to change the world for the better, if we want to cut through the hostility borne from polarization, sometimes we have to think again.

* Names of non-public figures were changed to protect their privacy.

Thank you for reading.

Interested in learning more? You can support me by:

- Purchasing Think Again, Originals, or Outliers

- Reading my last post: “We Have to Make a Decision: Better Police Training or Stricter Gun Control”

- Keeping up with my work on Instagram or Twitter

- Signing up for my mailing list below (on mobile) or the right side bar (on desktop)