Congressional Hearing

On June 17, 2014, Dr. Mehmet Oz, a Turkish-American, cardiothoracic surgeon and host of The Dr. Oz Show, appeared before a congressional hearing convened by the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Consumer Protection, Product Safety, and Insurance. Missouri Senator Claire McCaskill, the subcommittee Chairman, presided over the session titled “Protecting Consumers from False and Deceptive Advertising of Weight-Loss Products.”

Dr. Oz had been summoned because of criticisms that he was promoting unproven and unregulated weight-loss supplements with limited scientific evidence to substantiate the claims of the Florida-based manufacturer, NPB Advertising, Inc. (also known as Pure Green Coffee).

At the time, his show reached three million viewers a day and had won three straight Daytime Emmy Awards for Outstanding Talk Show, including two Daytime Emmy’s for Outstanding TV Host. His show had become so popular that a phenomenon known as the “The Oz Effect” had been colloquially termed, referring to the fact that any product featured on the show leads to a dramatic boost of sales.

The particular controversy surrounding The Dr. Oz Show that day stemmed from an episode aired in May 2012 where he had referred to green coffee bean extract as a “magic weight-loss cure” and a “miracle pill” that could melt away body fat. The endorsement allowed NPB Advertising, Inc. to sell half a million bottles of green coffee bean extract. The Federal Trade Commission followed up by suing the manufacturer for false advertising as well as Applied Food Sciences, Inc., the company that paid for a study purporting that the product causes weight loss without diet or exercise.

Dr. Oz defended himself at the hearing and pointed blame at Internet scamming and fraud. Under questioning, he emphasized that he does not sell anything, does not endorse any products, and makes no money from any products mentioned on the show. He pointed to the fact that this disclaimer appears at the end of every show. Further, he stated that his likeness and his words are often taken out of context by shady businesses to sell their products. In fact, he and Oprah Winfrey, whose show launched Dr. Oz into fame, have repeatedly filed lawsuits against companies for their transgressions. He also said that the problem

will begin to recede only when State and Federal agencies who have jurisdiction over the scammers amplify their enforcement and a public-private cooperative effort is undertaken in earnest that includes everyone on this panel in front of us, including the FTC, legitimate product manufactures, Internet ad-hosting services, and media outlets like mine. I need to be a part of this, I feel passionate about doing this, and I want to play a role.

Dr. Oz acknowledged making mistakes but maintained the intent was pure:

We constantly reflect as a show on which words are the right ones to use and which adjectives we may want to retire. We are always self correcting, progressing, trying to make a better show. Do we miss the mark sometimes? Of course. But our work is affirmed by the millions of e-mails, testimonials, phone calls, from people who say they saw something on our show that made a difference in their lives and they are better off.

He admitted that he did use forceful words like “breakthrough,” “magic,” and “miracle” when it came to green coffee bean extract. Unfortunately he went on to defend green coffee bean extract and state that he had at least five scientific papers backing up its effects, while simultaneously admitting that it probably would not pass FDA scrutiny. Later, he inadvertently made the point for the subcommittee that even after being “deliberately measured in our language,” another episode about a different product led to the similar levels of sales and the use of his likeness in Internet ads and articles the very next day. The Dr. Oz effect was very real, whether he liked it or not.

Ironically, while Dr. Oz admitted to not endorsing any products that are on the show, he also stated “I recognize that oftentimes they don’t have the scientific muster to present as fact.” However, he “personally believes in the items I talk about.” Even more, “I give my audience the advice I give my family all the time. I give my family these products, specifically the ones you mentioned. I’m comfortable with that part.”

Controversy Continues

Later in October 2014, the authors of the research paper on green coffee bean extract, originally published in the journal Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, retracted their study. Applied Food Services settled with the Federal Trade Commission for $3.5 million dollars. But the scrutiny only continued.

In December 2014, a study in the British Medical Journal, randomly selected 40 episodes from The Dr. Oz Show and The Doctors, another popular daytime medical talk show, in order to evaluate the advice shared on each program. They found that “approximately half of the recommendations have either no evidence or are contradicted by the best available evidence.” Further, the researchers of the article warned that the public should remain skeptical.

Controversy continued in 2015 when ten prominent physicians wrote to Columbia University, where Dr. Oz holds a faculty appointment, asking that his position be revoked. In a survey conducted by SERMO, a social network for physicians, more than a 1000 out of 1300 physicians agreed that he should resign, his medical license should be taken away, or both.

Working on The Dr. Oz Show

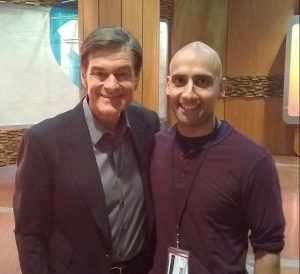

Wow. Talk about relentless. So what am I doing standing with Dr. Oz?

This past March, I participated in a medical school elective with The Dr. Oz Show in New York City. I knew the controversy surrounding Dr. Oz. I had heard other medical students and physicians refer to him as a quack and a fraud. But as a Communications major, I viewed the opportunity to learn how the world of television production worked. Besides, Dr. Oz is an undeniably great communicator. Being a surgeon is no easy feat either. Nor is winning an Emmy. So I was curious to see one model of “success” up close.

I was one of two visiting medical students participating in the month-long elective. The medical unit team we worked with was led by a medical unit producer, a licensed MD, and consisted of a medical associate producer and two medical student producers, roles funded by the show so that students could take a year off from medical school to work on the show full-time. The medical unit team worked on a variety of tasks not limited to pitching science topics for the show, scrutinizing the script for false statements, brainstorming ideas with the non-medical producers, writing articles for Dr. Oz’s newspaper columns, and looking up and verifying scientific facts and data in research articles from valid, peer-reviewed sources.

One brainstorming session with a producer gave me insight to the way the show worked. At one point, she asked me to come up with ways to treat chronic pain. Immediately, I responded with over the counter pain medication, like Advil or Tylenol, and ice packs. Just as quickly, I was shot down. The producer told me that they wanted new ideas. I replied that these therapies were the gold standard. This is what I was taught in medical school. This is what I would provide my patients. But she would not budge. We eventually came up with kinesiology tape and a homemade recipe for Bengay.

Truth versus Entertainment

From my very brief experience on the show, no one is trying to intentionally mislead the public. The medical unit team, especially, is dedicated to tilting the message of every episode towards truth. But the show finds itself plagued by the media’s unceasing drive to find the next new medical innovation. After nine seasons and over 1000 episodes aired, it is hard to come up with breakthrough ideas that are relevant and entertaining to, as it was explained to me, a specific demographic: middle aged, undereducated, unemployed, African-American females. At one point, a producer said to me that the creative challenge was trying to do the same show in a different way multiple times a season. And if you are working on the show, a place where you cut your teeth trying to make it in New York, and have earned your way to three million viewers an episode and multiple Daytime Emmys, do you want to change the formula that has worked? Do you want to lose the viewers? The sponsors? The show?

Like all television programs, The Dr. Oz Show is working within the limits of time, human attention, and language when presenting complicated, nuanced information to their viewer. The balance between truth and entertainment is a difficult one. But The Dr. Oz Show is not the only show that tries to walk the line. Anderson Cooper 360, Tucker Carlson Tonight, and even Last Week Tonight with John Oliver do this regularly. Their critics accuse them of pandering to their base. Do you think they have enough time to delve into every detail? Do you think they even want to?

Now critics charge that as a man of science, Dr. Oz should maintain a higher level of standard. I agree with this wholeheartedly. But it is probably easier said than done. There are no shortage of physicians ready to take up the mantle if Dr. Oz decided that every show would err towards pure, unemotional science. He would lose viewers. During his Congressional hearing, Dr. Oz even said,

When we write a script, we need to generate enthusiasm and engage the viewer. Viewers do not watch our show because they are seeking our dry clinical language. Viewers watch because we use language that is familiar to them which they would use when speaking to friends and loved ones. We are a guest in their home every afternoon. To treat that privilege like an academic lecture in medical school would be a miscalculation… Remember–people act on emotion and how they feel, so a main principle in building our scripts is to illicit a visceral, emotional reaction from the viewer.

I am surprising myself as I write this, but can we blame the show? Most physicians barely get 15 minutes with their patients. We interrupt them within thirty seconds. We spend most of that time with our eyes glued to the computer screen. And how enthusiastic are we? If we are in medicine long enough, we might get jaded and annoyed by patients. We will slog through our day and complain about the nurses. We might forget to write a prescription or mention an important side effect. Maybe we are so abrupt that the patient never tells us what is actually on her mind. Couldn’t our actions and attitudes also be misleading our patients?

I understand that being a doctor day-in and day-out is hard, but don’t think Dr. Oz’s job is easy. The show usually shoots two episodes a day, three times a week, 180 episodes a season. The day starts around 7 in the morning with a read through of the scripts and a medical briefing by the medical unit team. This is followed by dressing and makeup and rehearsal and then the shoots and probably a number of other details I was not privy to see. And from what I can tell, Dr. Oz is ON the entire time. He is engaged, asking questions, interacting with the audience, offering feedback about how to shoot certain segments, and extremely enthusiastic during the shoot. He is articulate and adept at speaking off the cuff, which as we can relate to in our own loves, gets him in trouble at times. And perhaps he gets ornery but I have never gotten to see it. The whole thing seems exhausting. But wouldn’t I love to try that job? Wouldn’t you?

To be honest, I am glad I went to NYC and I am grateful that The Dr. Oz Show gave me the opportunity to get involved. I encourage anyone who has the chance to take the elective because it is a great way to learn about how a television show gets put together. I also believe that the show does not need medical students to work, yet the producers and probably Dr. Oz thought it would be a good idea to show medical students a different perspective and even a different way to practice medicine.

Any Solutions?

But the concerns raised in the letter to Columbia University are extremely valid and relevant. We cannot despair that we do not have a voice when we can get more out of a face-to-face interaction than through the television. We can stamp out false medical knowledge with concerted effort:

- Take more time with patients. Listen to them. Hear them out. Give eye contact and look away from the computer.

- Continue to pursue creative passions as a doctor. Find a way to speak to local groups, write for your neighborhood newsletter, or share valid scientific information on social media. You can even start a blog, a podcast, or a YouTube channel. You can have a voice also.

- The Dr. Oz Show and other medical TV shows (including your beloved Scrubs!) undoubtedly have their flaws. Ask your patients where they get their health information from. Warn them about TV shows and unvalidated websites and social media channels.

- Find out if your patients are taking supplements. Tell them that they aren’t FDA regulated.

- Find ways to contribute to your local or regional medical association to put pressure on the companies that promote studies and products that are not backed by evidence-based medicine.

We are living in the age of false information and there is probably no way out. If we are actively media consumers, inform the people around us how to be media literate, and teach our patients how to learn about health (because they are going to look anyway), we can also tip the scales back towards truth. Now wouldn’t that be a bonafide breakthrough?